News Items - International Association of Packaging Research Institutes

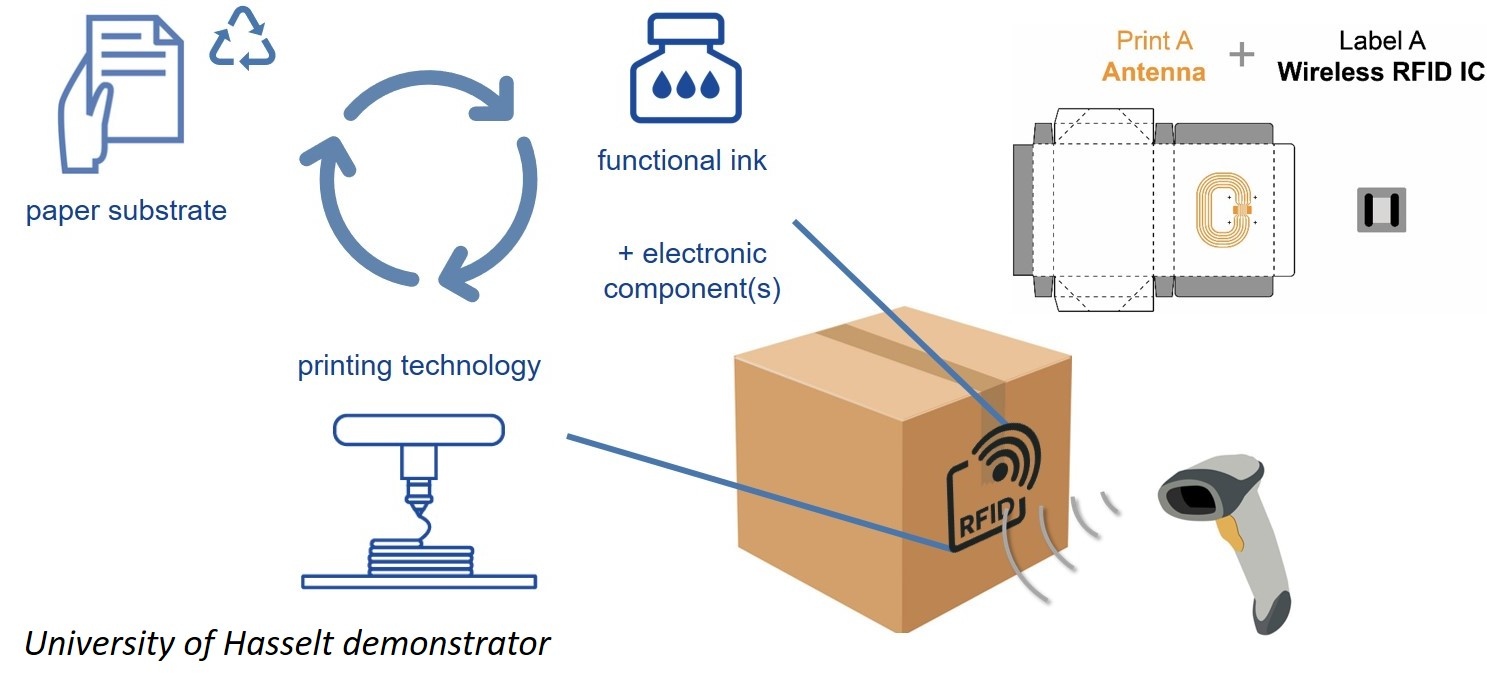

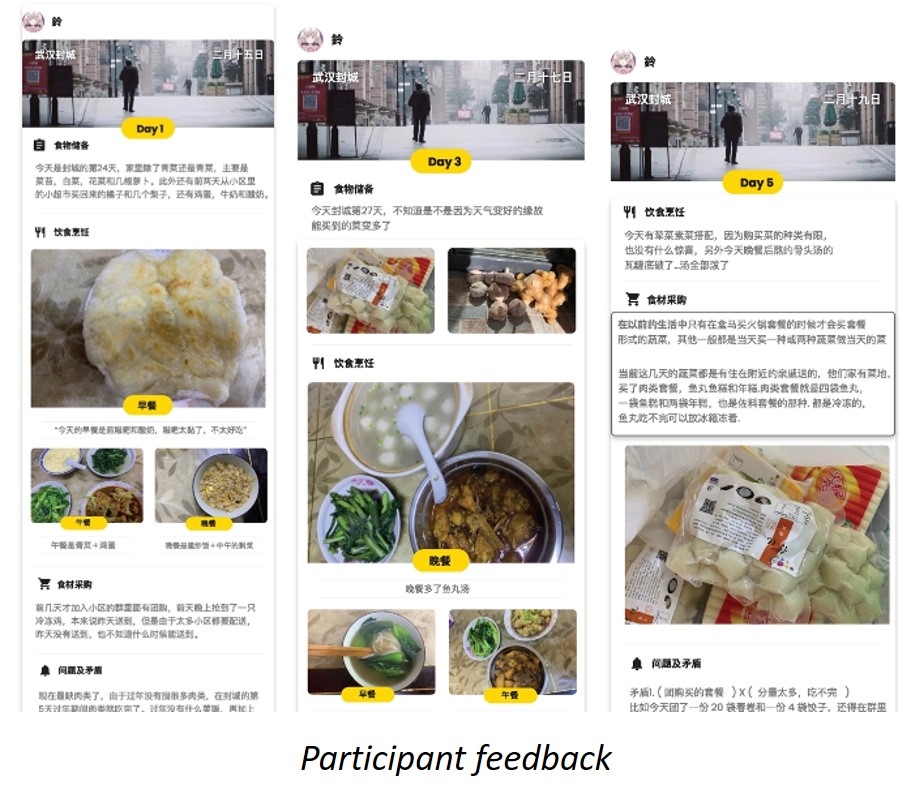

| Alternative routes to paper, research and intelligent packaging In the first of three selections from the busy June Conference program, we zoom in on wood-free paper alternatives, RFID options for board packaging and new methods for researching household food waste during lockdown As noted in last month’s preview, which galloped through the various themes in the IAPRI online Conference program, any detailed summary of the 45 papers would make for an extremely long article. But with the help of the moderators from the event, we have identified several which exemplify the quality and the variety of the Conference as a whole. We aim to outline these here and in subsequent Conference Spotlight articles over the next few months. It is also important to note that members who registered for the Conference can still access video recordings of all presentations online via the Whova app. New sources for paper One paper which was extremely well-received was delivered by Ravi Bohra, who is studying Organic Chemistry at SIES, Mumbai, India. He was part of a team researching the use of farm and vegetable waste to create wood-free paper. As he explains, the fact that India is an agriculture-based economy means the sector generates around 350 million tonnes of waste a year. Roughly one-third of biodegradable municipal solid waste derives from household kitchen waste. Meanwhile, globally an estimated 1.3 billion tonnes of food products are wasted every year. In an additional point, he notes that post-harvest stubble is typically burned in northern India, especially, contributing to dangerous concentrations of smog in cities such as New Delhi. “Our work aims to reduce the problem through a simple but effective method,” says Bohra, listing food and field waste as two raw material sources for wood-free paper. The route explored by SIES not only requires no chemical treatment, he says, but also constitutes an innovative method for reducing carbon footprint. There are further benefits, says SIES: this approach prevents deforestation, while also providing additional income for hard-pressed farmers. The slurry created from the different fibres acts as a paper pulp. In this case, it was put through the processes of washing, boiling, grinding, layering and drying.  “Because of the pandemic, not all types of waste could be accessed,” Bohra explains. In the end, five different types of waste were used to create four materials: pea waste; fenugreek; cowpea; and grass & banana peel.  The resulting substrates were put through a series of paper industry tests standardised by TAPPI. The resulting substrates were put through a series of paper industry tests standardised by TAPPI.In terms of thickness and grammage, the pea and grass & banana materials tended towards higher values, similar to paperboard, while the fenugreek and cowpea materials were closer to a type of tissue paper, he reports. There was negligeable elongation in the samples and poor tear resistance, in general. Nonetheless, the study concluded that papers could be produced simply and cost-effectively by further developing these techniques, benefitting from the natural bonding properties and rich textures which resulted from these raw materials. Future development would need to improve the strength of these papers, address issues of fibre orientation and thickness variation in the final product, says Bohra. Overall, the production process would need to be improved and standardised. Smart functionality for board Moving from the basic structure of paper to its more advanced functionality as a vehicle for active and intelligent (A&I) packaging, Mieke Buntinx of the University of Hasselt, Belgium, presented an update on the PAPERONICS project. This brings together six research partners and 34 industrial partners from Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany. Regarding the integration of fibre-based packaging with high-frequency radio frequency identification (RFID), Buntinx says: “One could visualize a shift from the use of external label components, as we know them, to fully-printed electronics in the future.”  A&I packaging is not the only growing market for printed electronics, but there are challenges, she admits. “So far, their production is expensive,” she says. “Many technologies are standalone solutions, and they’re often applied to plastics; the research landscape and supply industry for printed electronics are fragmented; and specific application scenarios using fibreboard substrates are missing.” A&I packaging is not the only growing market for printed electronics, but there are challenges, she admits. “So far, their production is expensive,” she says. “Many technologies are standalone solutions, and they’re often applied to plastics; the research landscape and supply industry for printed electronics are fragmented; and specific application scenarios using fibreboard substrates are missing.”The roughness of paper-based substrates and the impact this can have on the efficacy of inks may be one reason for this lack of applications. At a preliminary stage, the research looked at no fewer than 76 paper substrates and two silver inks. The aim was to create the optimum combination for screen printing an antenna, connecting a flexible, thin-film high-frequency RFID tag and then to design smart packaging demonstrators in three different applications. Tests carried out included Bendtsen air permeance, sheet roughness and sheet resistance. The Hasselt team also looked at the correlation between sheet roughness and resistance, on the one hand, and air permeance and sheet resistance on the other. The demonstrators were created using passive high-frequency RFID tags. The inks trialled were an Agfa Orgacon product and a less viscous Henkel Loctite ink. In this particular application, the Loctite ink appeared to perform better. Unlike other forms of digital gadgetry, most consumers do not have access to RFID technology, and the team took this into account in its choice of proposed demonstrators. Applications were limited to scenarios where RFID readers were in suitably close proximity to each tag. “Warranty abuse and incorrect handling of expensive electronic devices at the customer commonly occur, and retailers or manufacturers are held responsible,” says Buntinx, explaining the first prototype. “This issue can be addressed by integrating an encrypted RFID label into the box.” Different supply chain operators can store data on the tag. Several E-flute box designs were considered from the perspective of strength and security. A further prototype was developed for a reusable and foldable cardboard box, with an integrated RFID label for use in third-party logistics. The third application developed as a demonstrator was a software tool designed to support the logistics cycle. “Thanks to this tool, the status and real-time location of the box can be used for tracking and tracing product, and to optimise routing and delivery,” she says. Once again, paper substrates were selected with low porosity and low surface roughness, and screen printing was used to apply the HF antenna. “In conclusion, we can say that this multidisciplinary approach is a good example for the future implementation of hybrid electronics in sustainable, smart packaging solutions,” Buntinx says. Unpacking food consumption In the final paper revisited in this month’s selection from the online Conference, Wanjun Chu of Linköping University, Sweden, takes up the theme of ‘Unpacking consumer food consumption during a pandemic: methodological challenges when participants have to stay at home’. “If you ask people, some might say they generated more household food waste during lockdown, while others might say less,” says Chu, adding that studies, too, have shown conflicting results in this area. During lockdowns, many of the most-used qualitative research methods, such as field studies, participatory observation, contextual interviews and focus group discussions, were either difficult or impossible to organise. “My paper aims to explore the methodological challenges and opportunities for understanding food consumption and wastage behaviours, when participants and researchers have to stay at home,” he explains. Coincidentally, Chu himself is originally from Wuhan, China, where Covid 19 was first identified. So, it was doubly appropriate for him to set up trials of new research methods there. The case study involved seven households, and centred on two new techniques: Food Diaries and Letters to Food. In addition, semi-structured interviews were carried out. Different diary ‘probes’ were sent out to each household, covering areas such as comparisons between behaviour prior to and during the pandemic, food purchasing and preparation, and so on. The Letters to Food were based on the ‘love and break-up’ type of letter adopted in relation to consumer product use. “They’re encouraged to write this letter as if they are writing to a real person,” says Chu. In all, eight letters were generated by participants. Along with the diary entries, these then formed the basis for the semi-structured interview format.  The material collected was categorised either as ‘doings’ or ‘reflections’. In both cases, these could cover both food waste generation and prevention. Strategies that emerged included ways of ensuring large volumes of individual foods bought during lockdown were not discarded, were preserved in different ways or used in multiple meals. Other attitudinal changes included better meal planning and a tendency to value food more and be slower to discard it. “Reflecting on the method part of this case study, Diary Probes and Letters to Food not only served as a data-collection instrument, but also created a dialogue between researchers and participants,” says Chu. This situation arose because diary probes, in particular, were sent backwards and forwards on a daily basis, with the opportunity for tailored follow-up questions from researchers. Compared with questionnaires and surveys, the proposed methods demonstrated the strengths of dynamic data collection over an extended period of time - typically one or two weeks - he adds. Drawbacks of these methods included the degree to which individual household engagement with the process varied, providing different levels of data. “So, for example, when we see that participants show signs of lacking motivation for writing diary entries, we intervene and communicate with them and encourage them to keep at it,” says Chu. In conclusion, he says: “Even beyond the Covid-19 pandemic, we think that this proposed method has the potential to be adopted to uncover people’s complex behaviour in relation to waste and packaging.” Responding to an audience question, Chu noted that, given the strictness of the Chinese lockdown (where householders could not visit supermarkets and had to have all food delivered), the methods might require adaptation for other locations. Published: 06/28/21 |